Brooks Kelly stopped at a display of smart sprinkler-system controllers.

"This 6-station timer — it's got a rebate," said Kelly, who works the plumbing aisle at the St. George Home Depot. "You buy it [and the] Washington County water district gives a $99 credit to your water bill. So, this is free."

A conservation ethic is growing in the nation's second-driest state. The state requires all water districts to set conservation goals, and incentives like the rebates Kelly talked about encourage lower water use.

But Utah's also pushing forward with a plan to tap more water from the Colorado River to serve two counties in the southwestern corner of the state. And that raises at question: Does Utah really need so much water?

For Ron Thompson, general manager of the Washington County Water Conservancy District, the answer is "yes."

"No matter how you say it, the water is the key ingredient to any quality of life we want to have," he said.

St. George is the center of the fastest-growing metropolitan area in the country in the driest part of the nation's second driest state. It's an oasis in redrock country where the Colorado Plateau, the Great Basin and the Mohave overlap. Its location and its popularity present a big challenge: How to keep growing with limited water. It's a problem faced by the Mormon pioneers who settled this area.

"They were sent down here, and people told them they couldn't survive — but they did," said Thompson. "Told them they couldn't grow cotton — but they did. Told them they wouldn't stay — but they did. And that can-do attitude has permeated this culture here for 160, 170 years, and I still see it there."

For Thompson, working together on conservation now is important. But he's said for more than a decade that conservation alone can't support growth here, which is projected to swell from 165,000 population to 500,000 by 2060 .

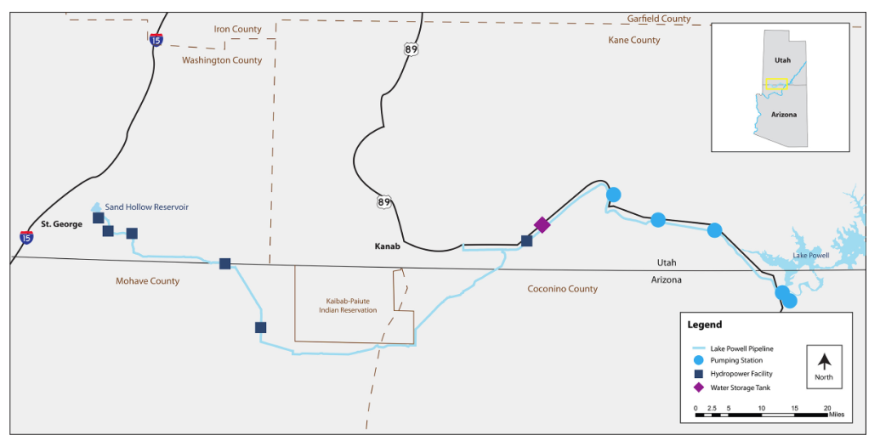

That's why Thompson has led efforts to build the Lake Powell Pipeline — basically a giant straw to draw Colorado River water over 140 miles of desert, halfway across the state. The project would deliver enough water for around 99,000 households, more than triple the current number. It would cost over $1 billion.

Developers of the West's big water projects like the Lake Powell Pipeline are sometimes called "water buffaloes." But Thompson has his own take on the term.

"I'm not sure I know what a water buffalo is," he said, "but if it's someone who's dedicated their life to water and realizes its importance to the economy and that it is fundamental to the quality of life we expect for ourselves and children, then I plead guilty."

Pipeline critics see Utah's water situation in a different light. They question whether the Utah lifestyle really requires so much water.

Looking at the numbers, it's a fair question.

The average person in the seven Colorado River Basin states uses 164 gallons per day (GPCD). Meanwhile, the state of Utah's GPCD is 214.

According to Utah's federal application for the Lake Powell Pipeline , the state justifies its request for the project by saying water use in the St. George area was 325 GPCD.

"The real elephant in the room is the price," said Nick Schou, conservation director for the environmental group, Utah Rivers Council. He said Utahns would consume less if utilities charged what water's really worth.

"We have the cheapest water that you'll find anywhere in the United States," Schou said.

KUER tested Schou's assertion by comparing a few by in the Colorado River Basin. The question was: What's the cost of 28,000 gallons of water, the average amount used by St. George residential customers in July?

In nearby Las Vegas, the bill would be $111 dollars. In Denver, $144. And, in Tucson, the one-month bill would be $235.

The picture in Utah is dramatically different. Salt Lake City customers are paying $75 for those 28,000 gallons in hottest month of the year.

St. George water customers pay less than $61.

Schou said Utah is decades behind in conservation.

"We're really looking at a legacy of destruction for water projects we don't need," he said. "And it's really a shame, because we have so many alternatives, so many different options to have a really prosperous growing community."

Back at the Home Depot in St. George, Roy Schell headed out of the garden section. He lives north of Grand Junction along the Colorado River and travels throughout Utah for job as a tech consultant.

Schell said he's surprised by all the turf he sees and all of the gushing sprinkler heads.

"We don't have enough water to not conserve," said the Coloradan.

Schell said he and his wife watch their water bills closely. And this year he's watched the water levels drop especially low on the Colorado, the resource residents of the seven Basin states rely on.

But here in Utah, it looks like people aren't as concerned. And he said that makes him "a little angry."

This story is part of a collaborative series from the Colorado River Reporting Project at KUNC, supported by a Walton Family Foundation grant, the Mountain West News Bureau, and Elemental: Covering Sustainability, a new multimedia collaboration between public radio and TV stations in the West, supported by a grant from the Corporation for Public Broadcasting.