Mitt Romney gave a major economic speech Friday, in which he stressed his plan to lower personal income taxes.

Romney's own taxes became an issue last month, when he acknowledged paying a lower tax rate than many middle-class families.

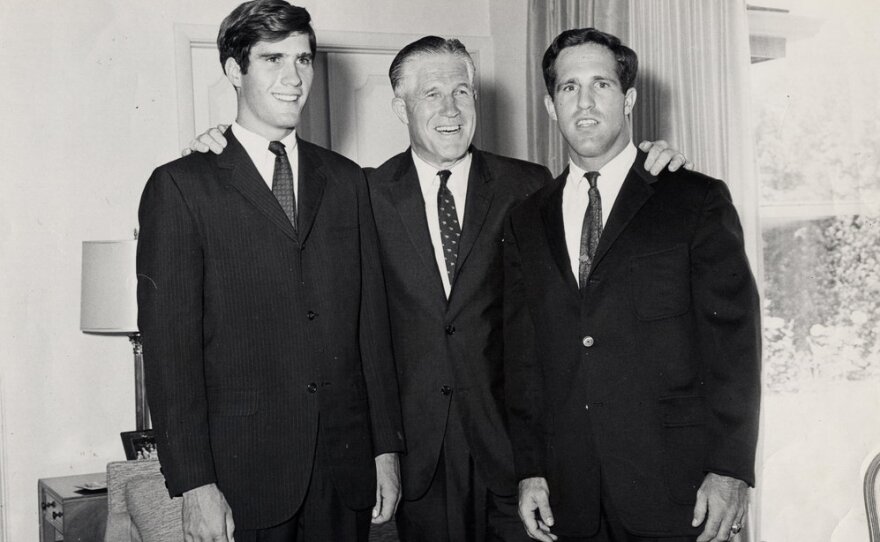

Friday's speech came in Detroit, where Romney's father made his fortune as an auto executive, before going on to serve as Michigan's governor. In 1967, during his own run for the White House, George Romney released more than a decade's worth of tax returns.

And in the lead-up to the South Carolina primary, pressure built on Mitt Romney to live up to his father's example.

"[George Romney] released them for not one year, but for 12 years. And when he did that he said this: 'One year could be a fluke, perhaps done for show.' When you release yours, will you follow your father's example?" asked CNN debate moderator John King.

Romney's reply: "Maybe."

Ultimately, Mitt Romney released just one year's return, 2010, as well as an estimate for 2011. His effective tax rate was just below 15 percent.

George Romney's returns tell a different story. His tax rate most years was two to three times that of his son. It topped 44 percent in 1963. That's the year the elder Romney was sworn in as Michigan's governor.

Big Shift In The Top Marginal Tax Rate

One big change between George Romney's time and our own is the top marginal tax rate. If you think tax rates are high today, think again — they were a lot higher in the 1950s and '60s.

The top marginal tax rate in 1955, the first year of George Romney's public returns, was 91 percent. Tax relief came along under Lyndon Johnson, but the top tax rate remained a whopping 70 percent.

"Definitely the 1960s were a different time than today," says Joseph Thorndike, director of the Tax History Project at Tax Analysts. "People were more comfortable with higher rates than we are today."

That comfort level would soon change, though, and for the next 20 years, the top income tax rate moved in one direction: down.

"It comes down to 50 percent in the 1970s," says Thorndike. "And then it drops down even further in sort of the mid '80s under Ronald Reagan to 28 percent."

A Preference For Capital Gains

But there were a lot of trade-offs to achieve this lower rate under Reagan. While taxes on ordinary income went down, taxes on investment income, like capital gains, went up. For the first time in modern history, money made for working and investing was treated equally. But it didn't last.

"Essentially since the beginning of the income tax there's been a preference for capital-gains income," explains Thorndike. "That's partly because economists thought it was a good idea. It's partly because politicians thought it was a good idea."

Bill Clinton restored the tax advantage for investment income, and George W. Bush made it bigger. Today, qualified dividends and capital gains are taxed at just 15 percent, less than half the top tax rate for ordinary income.

That's a big windfall for those like Mitt Romney, who make most of their money from investments. In 2010, nearly three-quarters of Romney's $21 million income was taxed at the lower capital-gains rate — a tax rate he defended at last month's CNN debate in South Carolina.

"I'm not going to apologize for being successful," said Romney.

George Romney also benefited from the tax discount on capital gains, especially in years like 1960, when his investment income neared $500,000. The elder Romney earned most of his fortune as head of American Motors Corp.

His son Mitt followed a different course.

"I could have stayed in Detroit like him and gotten pulled up in the car company," Romney said during the CNN debate. "I went off on my own."

The younger Romney made his money buying and selling companies for a private equity firm, Bain Capital. And that's another generational change. Finance, not industry, now dominates the U.S. economy, accounting for as much as 40 percent of all corporate profits.

"If you look at where smart young graduates from top schools want to go to work, a lot of it is in and around the financial sector," says economist Simon Johnson of MIT, who documents the change in his book 13 Bankers. "You hear some but not a lot of people saying they want to go work in manufacturing. But finance is still a huge draw for talent."

And those who do go into finance, like Mitt Romney, not only can make more money than their forebears in manufacturing, but they're able to keep more thanks to the design of the American tax code.

Copyright 2024 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.